Familiarity dulls the senses. Live in one place long enough, and you’ll see everything there is to see: the extraordinary becomes ordinary, the unfamiliar becomes routine, and surprises gradually fade away.

Think of your first ride on the New York City metro. Remember the unforgettable insights it has to offer into the spectrum of human behavior. Now imagine living there, enduring the metro commute every single day—day after day, week after week, year after year. Would you still be surprised at what you see during your daily metro ride? I haven’t lived in NYC, but I imagine that after enough time, you’d morph into a true New Yorker, unfazed by even the most creative displays of humanity.

This intuition can be summarized as follows:

Adaptation unfolds across various time scales (Fig. 1). Over evolutionary time, it is encoded in the genome and expressed through development. Within an organism’s lifetime, it is manifested in changes to synaptic weights driven by learning. On shorter scales, from hours to seconds, it is reflected in neural activity patterns, implemented through modulatory mechanisms1. In all these cases, a fundamental question arises: how much adaptation to the environment has taken place, and how can we measure it?

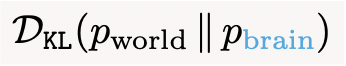

A principled approach to quantifying adaptation is through information theory. In this post, I will show how Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence—also known as relative entropy or relative information—can be used to quantify how much adaptation has taken place in a brain living in the world. Specifically, KL divergence measures the amount of information contained in the true probability distribution of the world that is absent from the brain’s internal “world model.” Don’t worry! I will make this concept mathematically precise as we go. Read on!

Outline

I will begin by explaining how survival depends on knowing the world around you. Acquiring this world knowledge isn’t a passive process. Rather, it involves making educated guesses, testing them out, and—most importantly—admitting when you’re wrong and updating your beliefs. In other words, adaptation is a constant cycle of generating hypotheses about the world, evaluating the likelihood of events, and revising the current hypotheses when predictions fail most of the time2.

Building on this line of reasoning, I’ll demonstrate how KL divergence (Kullback and Leibler, 1951) naturally arises in the mathematics of this likelihood evaluation. Next, I’ll show how this theoretical framework has far-reaching implications. For example, we’re going to derive pretty much all of machine learning from these foundational principles. No big deal.

Having established KL divergence as a privileged measure of distributional divergence, I’ll examine its key properties—particularly its interpretation as relative information—through an intuitive “Treasure Hunt” example. I’ll then explore why KL divergence is inherently directional, and explain how this asymmetry carries significant meaning for how we understand learning and adaptation.

Trust me, by the end of this post, you’ll reach enlightenment levels about KL divergence that you never thought possible. Your entire perspective on KL divergence is about to be transformed! Money-back guarantee 😉

To wrap things up, I’ll give you a neat summary using my signature “Math/English Correspondence” table, where I translate the mathematical results into plain English—pretty clever, in my humble opinion! I’ll also include a sneak peek at what’s coming in future posts (this thing grew out of hand: it turns out, to complete the story arc, I’ll have to publish 10 more parts, in addition to this one…).

Finally, I close with some wild speculations on how the framework I’ll establish here could unify all of science and philosophy as a single pursuit: humanity’s collective KL minimization.

Download PDF & Overview of Full Content

Alright, I should probably confess something: this post grew way beyond what I initially planned. The full version, complete with mathematical derivations, proofs, and detailed examples, spans 20+ pages. Rather than making you scroll through an endless blog post, I’ve decided to split it into two formats:

- For those interested in the complete treatment—including all mathematical derivations, intuitive examples, figures, and references—I’ve made the full 20-page PDF version available here:

- Here on the blog, I’ll continue with the high-level insights and conclusions, which actually work better in this format anyway.

Before we jump to the conclusions though, let me show you what you’ll find in the PDF version. Here’s the table of contents:

As you can see, we cover everything from the natural emergence of KL divergence to its interpretation as a measure of information gain, with plenty of mathematical meat in between. If you’re interested in the full mathematical treatment, definitely check out the PDF (and thank me later).

But for now, let’s continue here with the broader perspectives and key insights. I’ll summarize our main findings at a high level, and then we’ll discuss what’s coming next in this blog series. Don’t worry, even though we’re skipping the heavy math, the conclusions section will reference specific sections from the PDF, so you can always dive deeper into any part that catches your interest.

Conclusions, discussion, and a summary

Adaptation is the foundation of all biological systems, an omnipresent principle that defines life itself. Any biological system that persists, adapts. Why? Because adaptation is the very mechanism that enables survival, and survival, in turn, creates the opportunity for further adaptation. In other words, it’s a self-perpetuating feedback loop (Fig. 2):

In this blog post, we started by recognizing adaptation as the core principle underlying all of biology, and asked a simple question: can we take this fuzzy English term and give it a proper mathematical definition?

To this end, we chose a probabilistic framework (section 1 in the full PDF version). We then assumed the existence of two probability distributions:

- pworld: captures the structure and dynamics of the surrounding environment,

- pbrain: represents the internal subjective beliefs of a brain living in this world.

In section 2, we showed how simple logical steps, along with basic assumptions like having a large sample size, led us to our main theoretical result, eq. (7). This equation relates two seemingly distinct concepts to each other: On one side, the subjective probability your brain assigns to its observations, and on the other side, the KL divergence between the true world and your internal beliefs. Importantly, KL divergence naturally emerged in the derivations. We didn’t have to put it in by hand or assume anything else. This result demonstrates there’s something fundamental, unique, and privileged about KL divergence, setting it apart from other measures of probability divergence.

In section 3, we explored how the internal model, pbrain, works as a simulation engine for hypothesis testing. This sets up future posts where we’ll derive unsupervised algorithms for learning a pbrain, based on another (almost equally fundamental) principle of biological intelligence: prediction.

In section 4, we showed how pretty much all of machine learning can be derived from eq. (7). Our treatment gives new meaning to what’s really happening when you train a neural network: you’re adapting it to its world, defined by the empirical dataset it’s trained on. This raises fundamental new questions about world models, datasets, embodiment, and learning algorithms, all of which I plan to explore thoroughly in the future.

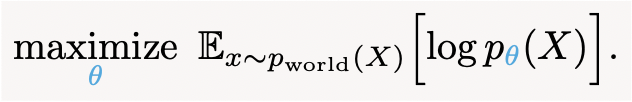

Additionally, our results from section 4 show how the main observation we started from—the vague English notion that “brains adapt to the statistics of their environments”—can also be made mathematically precise:

This turns out to be exactly the same loss function that generative models optimize. In other words, adapting to your environment is mathematically equivalent to learning a generative model of it.

Finally, in section 5, we explored how interpreting KL as relative information provides deeper insights into its directionality and meaningful asymmetry. We discussed how scientists extract novel information from the world by acting on it (i.e., performing experiments), resulting in a net reduction in our collective KL divergence. In this sense, both reading a book and performing experiments achieve the same goal: minimizing KL. This shows why defining intelligence at the individual level is insufficient; instead, humanity should be seen as a collective intelligence.

Summary table: Math/English Correspondence

As promised, here is the table summarizing mathematical results alongside an English translation:

Again, if you’re curious about the mathematical foundations behind any of these results—the proofs, derivations, and intuitive explanations—I encourage you to check out the full PDF version. There, you’ll find the complete mathematical treatment, including step-by-step derivations that show exactly how each of these insights emerges from first principles.

Future posts: a glimpse at what’s coming next

This is my first real blog post, and it holds a special place in my heart. I ended up covering a lot of ground here, and I deeply care about everything I’ve established. This approach captures how I think about the brain and intelligence—through the lens of information theory, probabilistic generative models, and physics.

This post was initially even longer. It grew out of hand so quickly. As I kept writing, I realized daaamn, I really do have a lot to say. So I decided to break these into multiple parts. But I couldn’t break this first one into smaller pieces. Everything here contributes to a single, cohesive message:

KL minimization.

Given the revolutionary consequences of this realization, I think it’s fine that this first post ended up being as long and comprehensive as it is. It serves a crucial role, laying the foundation for a ton of valuable stuff we’re going to develop later (insert: * obama-giving-himself-a-medal.jpg *).

Anyway, this post is Part 1 of 11, establishing the conceptual and mathematical foundations. Below is a quick overview of what’s on the horizon:

Part 2 – Insights from Dostoevsky

We’ll explore how Dostoevsky’s experiences in Siberian labor camps led him to recognize adaptation as the central theme of human existence. We’ll also explore the human desire to conform, interpreted as a side effect of this tendency to adapt.

Part 3 – What is pbrain anyway?

We will explore the subjective interpretation of probabilities, starting from Laplace’s take on probabilities as “common sense.” We will also examine some physicists’ attempts to make probabilities purely objective and discuss why such approaches fall short (a polite way of saying why they sound ridiculous).

Part 4 – Mental Representations, Maps, & Models: Insights from Tolman & Craik

We will trace the evolution of “Mental Representations” from philosophy to empirical science. We’ll examine Tolman’s revolutionary work on “Cognitive Maps,” and its subsequent validation by O’Keefe & Nadel. We will then explore Craik’s extremely prescient notion of “small-scale models” of external reality, which he introduced in his 1943 book, “The Nature of Explanation.”

Part 5 – Prediction: the core principle of (biological) intelligence

Craik’s idea that brains contain predictive models extends beyond neural systems to even single-celled organisms, which also exhibit predictive capacity—referred to as “Basal Cognition.” We’ll examine this universal principle of biological intelligence, laying the groundwork for understanding how intelligent systems learn their world models (pbrain) autonomously, without supervision.

Part 6 – Unsupervised learning of pbrain

We will follow Horace Barlow’s brilliant 1989 paper called “Unsupervised Learning,” on how brains extract knowledge from redundant statistical structure in their environment. We’ll also cover his later insights from a 2001 paper, “Redundancy Reduction Revisited,” where he invites neuroscientists to study pbrain as their main pursuit.

Part 7 – Intelligence feeds on redundancy

Building on Barlow’s insights, we will propose that lower-dimensional patterns in the environment enable intelligence to flourish. Reality can be broken down into a hierarchy of spatio-temporal scales, enabling our finite brains to grasp its complexity more effectively. This built-in, redundant structure echoes Wigner’s “Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics,” and is the underlying reason for the fundamental knowability of our universe.

Part 8 – Toward prescriptive neuroscience theories: The Free Energy Principle, ELBO, and the Principle of Least Action

In this inaugural post, I showed how most of machine learning can be unified under KL minimization (section 4, in the full PDF). What I’ve laid out here (sections 1 and 2, PDF) is the deepest layer of abstraction: from it come generative modeling (eq. (10)), and the ELBO, which is literally negative variational free energy. Some argue that Bayesian inference is the most fundamental theory, while others claim it’s free energy minimization. As we saw, both actually sit at the next level. In Part 8, I’ll explore this next level—encompassing ideas like perception as “unconscious inference”—building on the core ideas introduced so far. I’ll also draw parallels between this framework, and how the Principle of Least Action unifies all of physics.

Part 8 is going to be another deep dive, rivaling this post in scope and ambition. I can see it coming… But anyway, in Part 8, we’ll see how combining principles and prescriptions can yield real progress:

Part 9 – Selection: another principle of (biological) intelligence

Brains adapt not to random samples, but to actively selected ones. How you select your inputs almost entirely determines who you are. We will examine how selection shapes adaptation, introducing concepts of Embodiment and Umwelt—emphasizing how organisms adapt to their “self-world,” rather than “the world.”

Part 10 – Three lessons from biology

We will explore how biological principles can improve AI development. From the coupling of information processing and energy expenditure, to concepts like Embodiment, Umwelt, and active learning, biology contains a gold mine of insights that we can learn from. Just as Tolman, Craik, and Barlow’s ideas preceded and (indirectly) shaped modern machine learning, we can turn to biology, once again, for inspiration.

Final post: studying pbrain as the main thread of human inquiry

In the closing piece of the “World Models, Adaptation, and Surprise” saga, I will speculate, wildly, that pbrain is all there is, all there ever was, and all there ever will be.

Part X: All of science, including physics, is contained as part of pbrain

Science is a process of collective KL minimization. Whenever you read a physics textbook, you update your pbrain, which results in a net reduction in  from eq. (7). This, in turn, allows you to better predict the real world around you:

from eq. (7). This, in turn, allows you to better predict the real world around you:

For example, the trajectory of a projectile (using Newton’s laws), or the dynamics of a quantum spin in a magnetic field (using Schrödinger’s equation)3.

By studying pbrain—that is, by studying how our brains build and refine probabilistic models of the world—humanity can tackle the most fundamental questions: How do we perceive and think? How does the brain implement these processes? How do our mental models link up with physical reality? This is how pbrain bridges philosophy and science.

Therefore, studying pbrain is the main thread of human inquiry. The crucial questions we must ask about pbrain, the “engine” of our perceptions and decisions, include: How is it implemented in a network of spiking neurons? How is it updated and maintained? And how does pworld, and its redundant structure, shape and constrain pbrain? This line of investigation will reveal fundamental truths about ourselves, the physical reality around us, and the relationship between the two.

This perennial quest4 to understand our internal models of reality has been around since at least the ancient Greeks, and continues with us today. But now, we have a clearer conception of the core problem, and a mathematical framework to guide us in this ancient pursuit.

The answers will come. I’m certain of it. Join me, and let’s minimize our collectiveKL divergence.

Acknowledgments

The initial ideas and draft for this post were sampled from phadi(X), then refined with AI assistance. I want to thank Claude and ChatGPT for helping me edit this post through rounds of back-and-forth conversations, as well as for their help with custom CSS and HTML code.

Download PDF, code for generating figures

Code for generating the figures:

Footnotes

- Biology is wild and unfathomably complex. Each timescale mentioned here involves additional key mechanisms: evolutionary adaptation includes epigenetic regulation and gene expression dynamics; learning encompasses non-synaptic cellular changes including protein synthesis and receptor trafficking; and rapid neural adaptation relies on both modulatory and ionotropic mechanisms, including ion channel dynamics and neurotransmitter kinetics. ↩︎

- Closely related to the “FAFO principle”: Fuck Around and Find Out. ↩︎

- Here’s a simpler summary: Our minds hold a probabilistic model of reality. Learning (e.g., reading a physics textbook or conducting experiments) updates that model, closing the gap between what we predict and what actually happens. In this inaugural post, we formalized this “closing of the gap” as “KL divergence minimization”. ↩︎

- An homage to my favorite Death song, featuring sophisticated riffs, unforgettable lyrics, and an ethereal outro that perfectly captures the sentiment echoed in these closing lines. ↩︎