Every breath you take, every move you make, every glance you steal—literally all the time—there is something going on behind the scenes: your brain is running billions of calculations to answer one question… what the hell is actually happening right now?

Being alive means dealing with uncertainty, every moment of every day. Seriously, that’s what it means to be alive: to navigate uncertainty, to try to “infer” what’s going on, using only limited and noisy information. We need to be able to understand this complex and uncertain world around us, at least well enough to survive and reproduce.

But what does it mean to “understand” the world? It turns out this can be rigorously mathematized as Bayesian inference. Don’t worry! I’ll develop every intuition from the ground up and slowly derive the math from scratch. No background needed whatsoever.

By the end of this post, I hope to convince you that:

| inference | = | understanding the world |

| the brain | = | electric meatball inference machine |

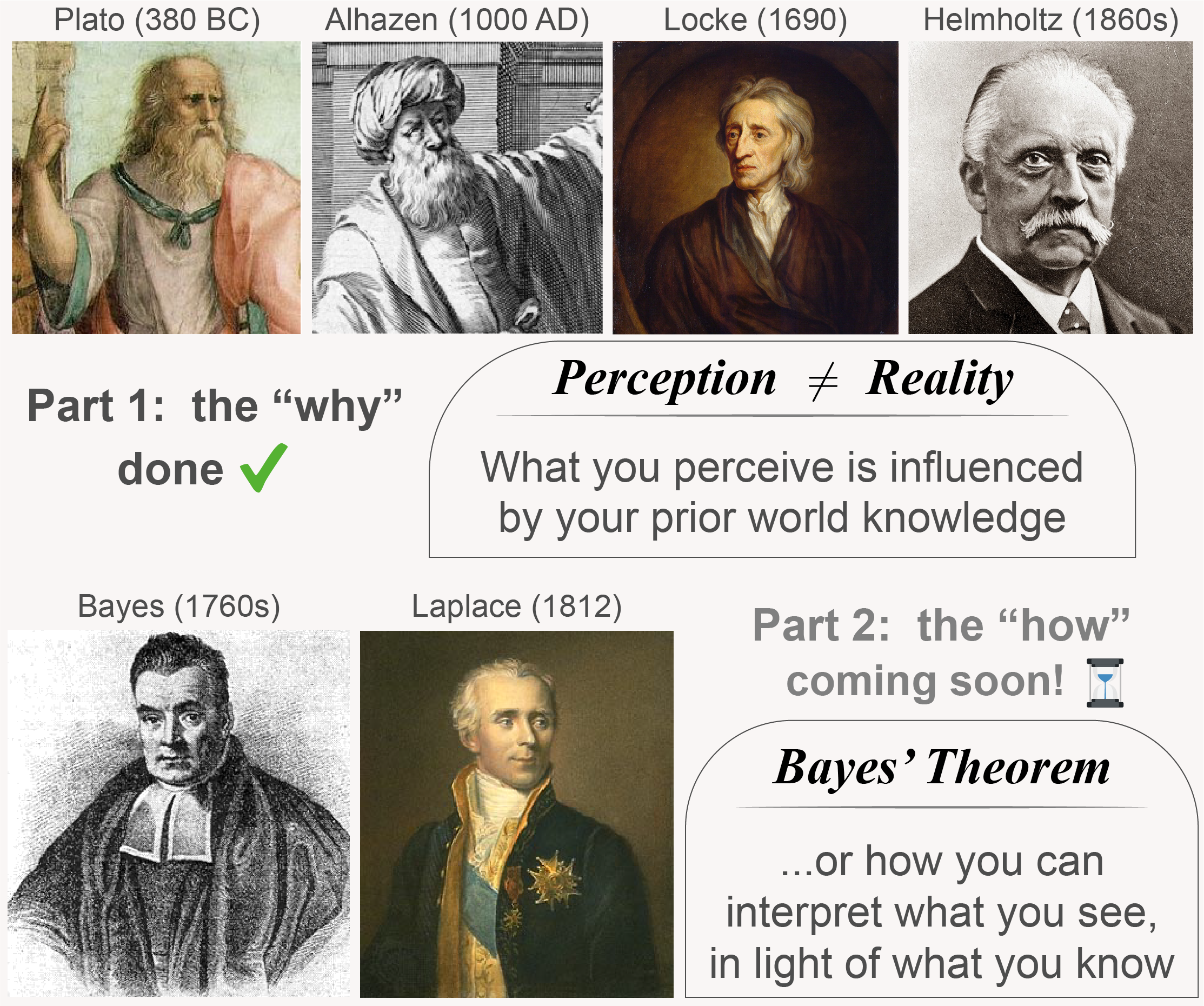

Our journey begins with three intuitive examples of inference from everyday life: rain, vision, and language. Using these as our foundation, we’ll explore the concepts of uncertainty and probability, touching on the pioneering work of Bayes[R1] and Laplace[R2]. Finally, we’ll travel back in time to show that the problem of perception has captivated thinkers and philosophers for millennia.

This post is about addressing the “why” — it acts as a conceptual launchpad with minimal math. Future posts in this series will build on the groundwork laid here, guiding you from intuition to equations. We’re going to tackle everything from optical illusions to the complexities of social life, all understood through the mathematics of Bayesian inference.

Contents

- (1) Inference in action: 3 examples of increasing difficulty

- (2) Uncertainty, the omnipresent antagonist

- (3) Probability, the calculus of common sense

- (4) Quantifying uncertainty using probabilities

- (5) Perception ≠ Reality: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

- Conclusions

- Download as PDF

(1) Inference in action: 3 examples of increasing difficulty

What is inference? It’s your brain trying to guess the hidden causes behind what you observe. In this section, I’ll unpack this idea using three intuitive examples, each one harder than the last:

- You see wet ground ⇒ Was it rain?

- You see a round shape ⇒ Is it a circle or a sphere?

- Someone says something to you ⇒ What do they actually mean?

Alright, let’s explore these examples in their dedicated sections below.

(1.1) Beginner: inferring whether it rained from seeing wet ground

Imagine a crisp autumn morning. You wake up and brew yourself a rich, steaming espresso. Then you step outside on the balcony to enjoy it, as the cool morning breeze brushes against your face. While savoring that first sip, you notice the ground is wet, and you immediately think: “Ah! It must have rained last night.”

That right there, my friend, is inference: you didn’t directly see the rain itself, but its consequence, the wetness of the ground, led you to infer that it must have rained. In other words, you saw some evidence and guessed its underlying cause. Simple as that!

But hold on, is it really that straightforward? What else could have made the ground wet? What other explanations might account for what looks exactly like the aftermath of rain?

Now let’s imagine a made-up scenario. You live in a film town (you know, one of those places where movies get made all the time), and your neighborhood sometimes has movie shoots. Some of those movies have bittersweet goodbye scenes with fake rain added for dramatic effect. Because of this, sometimes when you look outside, you see wet ground that wasn’t caused by actual rain, but by cinematic trickery.

In this case, you can’t be absolutely certain that every single instance of wet ground means it rained. You’d need more information. Maybe you go outside and walk around a little. If the wetness is oddly localized and limited, then you can be more confident it was just a movie scene.

But now that we’re imagining things, why stop there? Maybe you’re the type who enjoys a little fantasy with your espresso. For example, you might imagine the wetness was caused by the tears of a heartbroken giant, crying his eyes out. Is that likely? No. But your brain doesn’t instantly rule it out. It quietly keeps it in the list. Because that’s what inference is: weighing possibilities, even ridiculous ones, according to your weird little belief system.

This shows that even a trivial inference problem like guessing what caused the wet ground can get surprisingly tricky. The deeper point is that inference is fundamentally subjective. It depends on you: your past experiences, your fantasies, your beliefs, your personal history. All of this shapes how you “perceive” the world and make sense of what’s in front of you.

In another post, I’ll introduce Bayesian probability theory from basic first principles and make all these examples mathematical and rigorous. Just wait and see! It’ll be fantastic. The best.

For now, let’s keep going with inference examples. This will show us the full extent, generality, and applicability of the inference problem. Yeah, it’s basically all you do while being alive. I insist!

(1.2) Complex: inferring the 3D world from 2D visual inputs

Time to explore my favorite topic: vision. Before introducing the specific inference example I’ve prepared for you, let me first emphasize how damn difficult the task of vision is[R3]. The challenge isn’t very obvious, because we just open our eyes and see. But what happens during this process?

(1.2.1) How does vision work?

We see by detecting light patterns made of photons. These photons reflect from objects in the physical world and land on the retina, a two-dimensional sheet of neurons at the back of your eyes. Retina is quite special, because it’s the first and only part of the visual system that makes direct contact with the physical reality. After absorbing these photons, the retina processes them, converts them into electrical signals, and sends those signals to the brain for further processing.

After that first hit of photons, it’s lights out. From there, it’s just electrical activity zipping around in the dark. No images, no colors. Just voltage. And yet, your brain, this magnificent inference machine, somehow turns electricity into rich visual experiences. Like the redness of a cherry, a glowing sunset, and the face of someone you love.

Those are all constructed in your brain. From nothing but electric impulses. It’s pure magic!

(1.2.2) The challenge: interpreting the 3D state of the world from 2D retinal inputs

Now let’s focus on a specific challenge within visual perception. The world is made of 3D objects. The retina, on the other hand, is a 2D sheet. How does the brain perceive the world as 3D, even though it only receives this lower-dimensional 2D projection of it?

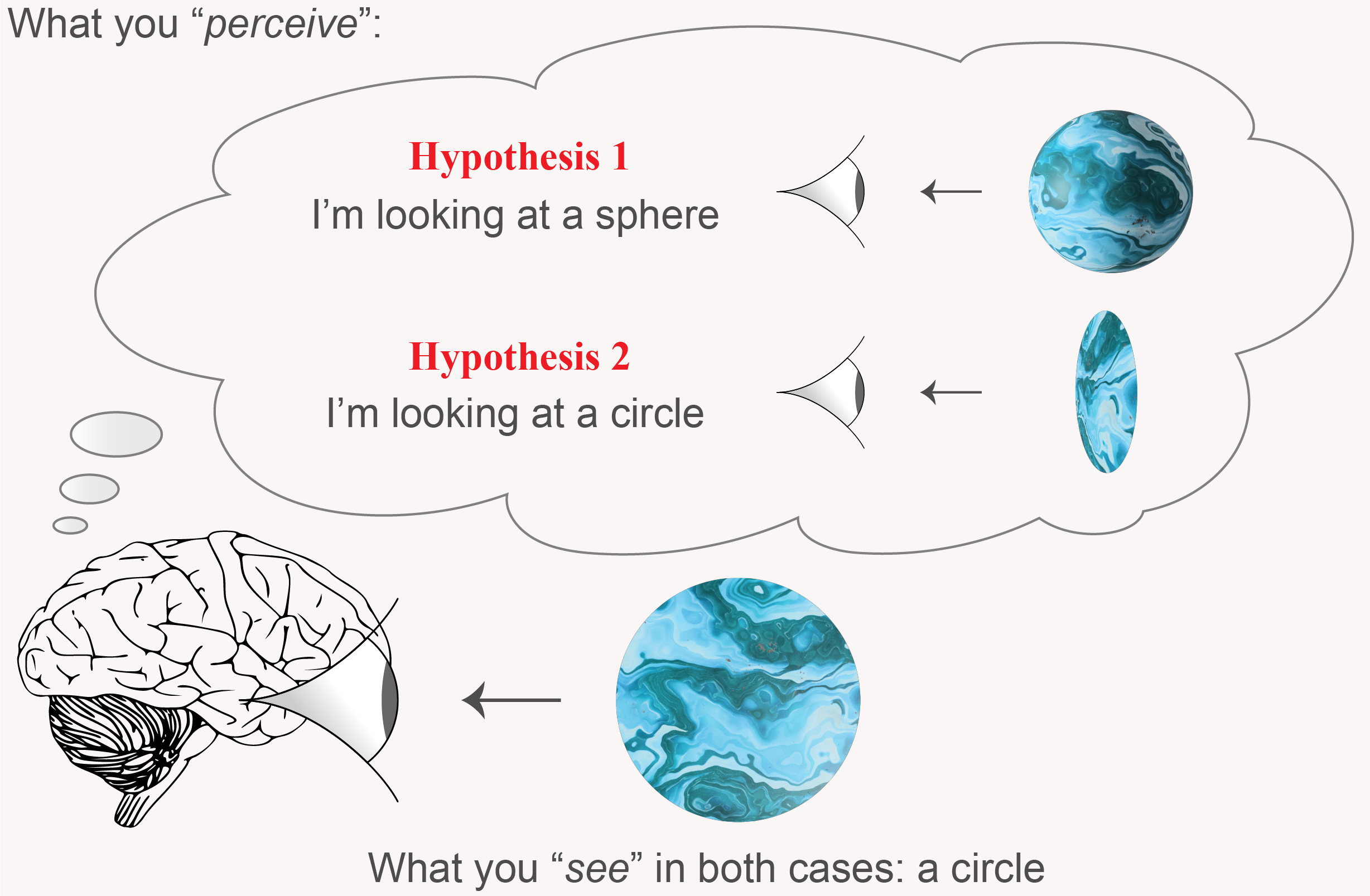

Let’s further unpack this using a very concrete example. Suppose you are looking at a circular shape. What is it? It could be a 3D sphere. Or it could be a 2D circle, held perfectly perpendicular at the direction of your gaze (Figure 1). Sure, it feels like it’s probably a 3D sphere. But where does that intuition come from? How does your brain decide?

The broader challenge here is that vision suffers from the degeneracy problem: many different world states can generate the same 2D pattern of light. In other words, there is a many-to-one relationship from world states to the sensory stimulus received by the brain. And your poor brain has to pick the correct interpretation from this incomplete signal[R4].

Yet again, our vision is quite reliable, and we have survived so far. That means evolution has found a way. But what is it? Can you guess? Say its name… Yes! You’re goddamn right: it’s inference!

It’s your brain’s process of combining vague sensory inputs with your prior world knowledge to conclude like this: “I am looking at this circular shape. It could be a sphere, it could be a circle. But I have seen many more spheres in the past, so it’s more likely to be a sphere.“

(1.2.3) Quick history detour: Locke, Helmholtz, and Alhazen

By the way, if you think I made up this example, think again. I was a bit late to the party. Someone thought about this particular inference problem back in 1690 (only 90s kids will remember…). That’s right. This circle versus sphere example comes straight from John Locke’s magnum opus, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding[R5]. Here’s a directly relevant quote from the book:

Locke’s emphasis on “grown people” is about accumulated world knowledge. In Bayesian inference, this is called the prior knowledge. And what he calls “judgment” can be thought of as the final outcome of the inference process — which, later, we will learn it’s the posterior. Finally, his phrase “without our taking notice of it” means that perceptual inference happens unconsciously.

It’s uncanny how Locke anticipated these ideas, long before Bayesian inference was a thing (Thomas Bayes was only three years old when Locke died in 1704). Nearly two centuries later, Hermann von Helmholtz, drawing on both Locke’s philosophical insights and his own psychophysics experiments, introduced the now-famous phrase, “Perception as Unconscious Inference” [R6].

Here’s a quote attributed to Helmholtz that perfectly captures this idea:

Finally, these ideas also go back to over 1000 years ago, to Ibn al-Haytham (or Alhazen), who was the first to argue that vision occurs in the brain rather than the eyes[R7]. He was also the first to point out that personal experiences affect what people see and how they see, and that perception is ultimately a subjective experience.

If you read his book, Alhazen was almost a few inches away from saying “unconscious inference” himself. Clearly similar vibes to Helmholtz! I might write another blog post exploring this rich history in more depth. But that’s enough for now.

Before moving on to the next inference example, let me show you how this world knowledge thing can be totally different for different people (or Aliens with magnetic brains).

(1.2.4) Priors and Prejudice: a tale of magnetic Aliens and spherical fruits

Let’s now imagine another made-up scenario: an Alien civilization living in a galaxy far away.

The Alien planet has a very limited plant diversity. They only have two types of identical-looking trees. One of them produces delicious, spherical fruits. The other produces 2D circle-shaped fruits that are poisonous to eat, but not to touch. Interestingly, these circular fruits also respond to magnetic fields around them. Whenever they detect even the faintest of magnetic fields, they rotate so they are always perfectly perpendicular to the direction of the surrounding field.

Meanwhile, these Aliens have haloed brains that produce a strong magnetic field around them, which annoyingly interacts with the circle fruits. This is unfortunate, because whenever these Aliens are around, the circle fruits rotate and become perfectly aligned with their direction of gaze. Because of this effect, the Aliens always see perfect circular shapes, but have no way of telling if it’s a rotating 2D circle or just a 3D sphere.

As you can imagine, this is a very frustrating situation for the Alien kids who want to pick fruits on their way to school. They encounter these trees left and right, but have no way of telling which fruit is which. They all look like a circle, all the damn time. Their only way of disambiguating this is to walk up to the trees and touch the fruits. That way, they can reduce this unbearable uncertainty, making sure a fruit is nutritious and spherical rather than poisonous and flat, before they eat it.

As far as the Aliens are concerned, any circular pattern they encounter has an equal probability of being a circle or a sphere. This is quite unlike our experience growing up here on Earth. As a result, these magnetic Aliens develop very different prior world knowledge from us humans. Consequently, their perceptions (= inferences) are also totally different from ours.

Here’s the main take-home messages I want you to remember:

- The challenge: Vision is difficult because the sensory signals are incomplete, noisy, and degenerate.

- The solution: The “grown people” brain’s job is to use its prior knowledge of the world to break the symmetry between competing interpretations, and settle on the one that makes the most sense.

- Priors are history: This prior knowledge is subjective, shaped by our evolutionary history and personal life experiences.

Let’s now explore our final inference example. Time to hit you with the real deal: social inference.

(1.3) Ultimate: inferring other people (and even yourself)

Earlier, I claimed being alive means dealing with uncertainty. But the world we need to understand isn’t just rocks and trees. It’s filled with other humans, carrying around the most complex organ in the known universe—a human brain. These all singing, all dancing biological supercomputers produce wildly unpredictable behaviors, stemming from billions of spiking neurons. We can’t measure those neurons, and even if we could, we wouldn’t know how to decode and interpret them.

So we’re left with a brutally difficult inference problem: understanding other humans solely based on their words, gestures, and facial expressions — some noisy, compressed, and unreliable signals. It’s like trying to understand the inner world of a supercomputer by watching its screen flicker.

And yet, somehow we manage. You’re here, reading these words right now. This means our ancestors figured out how to infer other people’s mental states well enough to survive, cooperate, and convince each other to reproduce. This is genuinely remarkable given the computational complexity involved 1 .

In linguistics, this broader challenge falls under pragmatics[R8], the study of how context contributes to meaning. That is, extracting meaning beyond literal words requires knowing the speaker as a person, their cultural background, and other contextual information. For example, when someone says “this blog post is really interesting,” they might genuinely find it fascinating, or they might be politely humoring you, or they might be subtly asking you to stop yapping about Bayesian inference every damn time you hang out. Successfully deciphering the true meaning requires a sophisticated model of the speaker’s personality, their likely intentions, the social situation, and countless implicit shared understandings about how communication actually works.

Given all this complexity, I suspect we must have evolved highly specialized neural circuitry for rapid social inference. Otherwise, the computational requirements would be staggering. The physical world is forgiving in comparison. A rock doesn’t change its properties based on who’s asking about it. Mathematical equations remain true regardless of the mathematician. But people? They’re unfathomably complex, context-dependent, and beautifully unpredictable.

Here’s where it gets even stranger: you might even be performing Bayesian inference on yourself, trying to infer your current internal state based on the signals entering your conscious mind. These signals, also known as gut feelings, are almost certainly a lower-dimensional projection of the enormous processing that’s going on subconsciously. But let’s not go there (maybe another post).

All I wanted to communicate in this section is that social inference is perhaps the ultimate test case for understanding how our brains perform Bayesian inference… The most complex organs in the known universe, performing inference on each other, under extreme uncertainty 2 .

(2) Uncertainty, the omnipresent antagonist

I recently stumbled upon a post on X, where someone asked ChatGPT 4.5 for a deep and novel insight into the human condition. Here’s what it had to offer:

I must admit, this is pretty accurate. Well done, ChatGPT 4.5! Although I don’t think this is a novel insight, a lot of people don’t appreciate this point deeply enough: that happiness emerges when we momentarily defeat uncertainty, the main antagonist in our lives. I’ll explain why shortly.

But first, what is uncertainty? It’s something you feel. When you observe the wetness of the ground and remain unsure whether it was real rain or cinematic trickery that caused it. It’s what Alien kids grapple with when faced with perfectly identical circles, unable to distinguish between nutritious spherical fruits and lethal poisonous impostors.

Sometimes, the stakes are low, like the rain example. You can easily deal with that uncertainty. Who cares if it was real or fake rain? You sip your coffee, shrug it off, and get ready to go to work. Resolving this uncertainty doesn’t alter your life in any significant way. Other times, the stakes are high, but still manageable. Like the Alien fruit example. You just walk up to the tree, touch the fruit, and fully resolve the uncertainty.

The rain or fruit examples are not the type of uncertainty ChatGPT 4.5 is talking about. These are just fun, made-up scenarios. So, what is that quote about, then? It’s about people.

People… Oh, boy. If uncertainty were to take a physical form, it would be human-shaped (or maybe sometimes cat-shaped!). Since you’re reading this, you’re likely not a serene monk isolated in a remote cave, blissfully removed from human complexities. Those lucky few aside, social uncertainty is the true antagonist for the rest of us. It’s the final boss of Bayesian inference 3 .

Time to think about uncertainty more systematically. Can we quantify it? Or is it just a vague, slippery feeling we happen to experience? Our goal is to make it concrete, by translating that foggy feeling into clean, computable math 4 .

That’s exactly what we’re going to do next.

(3) Probability, the calculus of common sense

What is probability? Before I give you my take, let’s see what other thinkers before me had to say about this:

Fantastic… The most important concept in science that nobody understands also happens to not exist at all. How unlucky for us, right? Not really. That de Finetti quote is about objective existence. As in, probability does not exist in the same objective sense that apples exist[R11]. Instead, de Finetti subscribes to a subjective interpretation of probability: it’s about you, your feelings of uncertainty, your ignorance, your interpretations of the world.

This subjective interpretation of probability has been around for a long time. It goes back to the original visionaries, Thomas Bayes and Pierre-Simon Laplace, who developed these ideas in the 18th century. Around 1763, Bayes introduced a method for inferring the causes behind observed events by combining new data with what you already know [R1]. His work, published after his death, laid the foundation for what we now call Bayesian statistics.

A few years later, Laplace came across similar ideas and spent decades developing them further. He applied this way of reasoning to everything from astronomy to everyday decision-making, showing how it could be used to make sense of uncertainty in a clear, logical way. This quote from his 1812 book captures this idea beautifully:

There you have it, folks. Probability is about taking those feelings of uncertainty, the instincts, the common sense, and turning them into something you can calculate. I don’t know about you, but I only understand what I can calculate. Which is perhaps why I am so fascinated by humans. They are so incalculable, so beyond the grasp of my finite, simple brain… Okay, let’s not go down that rabbit hole again. We conclude that probability is nothing but a calculus of common sense.

I plan to introduce Bayes’ theorem in a future post and prove it using intuitive visual methods. But for now, let’s explore how we can use numbers to represent our uncertainty.

(4) Quantifying uncertainty using probabilities

Recall the rain example from above. In the simplest case, you live in a normal neighborhood, where extensive wetness of the ground can only be caused by actual rain (or tears of a heartbroken giant). In this case, you might use the following probabilities to numerically express what you believe likely caused your observation:

| pbrain( actual rain | I saw wet ground, and I live in a normal neighborhood ) | = | 0.99 |

| pbrain( giant tears | I saw wet ground, and I live in a normal neighborhood ) | = | 0.01 |

You might wonder about that subscript, brain, in the probability function. That just means your brain assigns these numbers. For example, my phadi(⋅) might be very different than your pbrain(⋅) — let me clarify: functionally, phadi(⋅) works just like any pbrain(⋅), since it follows the same probability rules (same math, same logic). But the numbers can be wildly different if our beliefs about the world diverge.

About the colors, I use red to indicate causes, and green is for observations (also called evidence). You directly see evidence, and infer the probability of causes. In English, each line reads like this:

Also notice that this example is a trivial inference problem, where you have near-perfect certainty that it must have rained. You still consider some unlikely alternatives, but you’re 99% sure the best explanation is just rain.

Finally, see how those probabilities add up to 1? This is because a probability of 1 represents total certainty. For this rule to apply, our list of causes must be exhaustive, meaning it includes every possibility we’re considering. We are 100% certain that one of these causes must be the true one, and we simply divide that total certainty among them.

In other words:

Technically, pbrain( cause | observation ) is called a posterior probability distribution in Bayesian statistics. The term “posterior” is used because this distribution reflects your updated beliefs after observing evidence. And no, despite the name, it has absolutely nothing to do with anatomy.

Let’s keep going with the rain example. Now I want to demonstrate how your past experiences directly influence how you distribute your belief budget across different possible causes. Imagine you have lived in the film town for the past year, and you saw wet ground for a total of 100 days. Out of those 100, you later learned that 75 were caused by actual rain, 24 were fake cinema rain, and one time, you never figured out what actually happened. In this case, right after seeing wet ground this morning, you might form the following beliefs:

| pbrain( actual rain | I saw wet ground, and I live in a film town ) | = | 0.75 |

| pbrain( fake rain | I saw wet ground, and I live in a film town ) | = | 0.24 |

| pbrain( giant tears | I saw wet ground, and I live in a film town ) | = | 0.01 |

You get the idea, right? The main point: probabilities are ultimately about how uncertain you feel about something, which is shaped by your experiences having lived in the world. Your neighbor, who just moved in yesterday to a film town, would still have something like a 99% certainty about real rain. Just give them time. Let them experience what it feels like to live in a film town. Their beliefs about the world will evolve to become closer to yours, which is a better model of reality.

Before wrapping up this section, I wanted to revisit the pragmatics problem in linguistics[R8], and show you how this can also be framed as Bayesian inference. Let’s imagine you read this post and gave me the following feedback: “this blog post is really interesting.”

If you’re sarcastic, I might form somewhat skeptical beliefs about what you really meant:

| phadi( you genuinely find it fascinating | your feedback, you’re sarcastic ) | = | 0.50 |

| phadi( you are politely humoring me | your feedback, you’re sarcastic ) | = | 0.10 |

| phadi( stop obsessing about Bayes, get some help | your feedback, you’re sarcastic ) | = | 0.40 |

But, if I know you as someone who’s thoughtful, values social harmony, and takes care to consider your words and their impact before speaking, then that would completely shift how I interpret your feedback:

| phadi( you genuinely find it fascinating | your feedback, you’re thoughtful ) | = | 0.95 |

| phadi( you are politely humoring me | your feedback, you’re thoughtful ) | = | 0.04 |

| phadi( stop obsessing about Bayes, get some help | your feedback, you’re thoughtful ) | = | 0.01 |

Overall, when you find yourself reading between the lines, trying to figure out what someone actually means, remember this: you’re just performing inference. Every human interaction is a dance of uncertainty, trust, and context. And our brains are dancing right along, often “without our taking notice of it” (as Locke would put it).

(5) Perception ≠ Reality: Plato’s Allegory of the Cave

Here’s where everything comes together, so pay close attention! In all three inference examples, you never have direct access to reality. You never know what actually happened with full certainty. But you infer the likely causes based on what you observe, and what you already know. There’s another name for this process of going from observations → causes. It’s called perception.

When you see wet ground and infer that it must have rained, that’s your perception of what likely happened. There’s no guarantee it matches reality. When you see a circular shape, you use your world knowledge that spheres are much more common than flat circles. So you infer that what you’re seeing is most likely a sphere. But it’s a totally different situation for the Aliens, since spheres and circles are equally common on their planet. As a result, your perception of a circle—the inference you perform—is wildly different from that of the Aliens.

Similarly, when you interact with other humans, you never truly know what’s in their minds. Chances are, they themselves aren’t even fully aware of all the subconscious processing influencing their thoughts, mood, and behavior. We have no other choice but to settle for this indirect, subjective perception of other people (and ourselves).

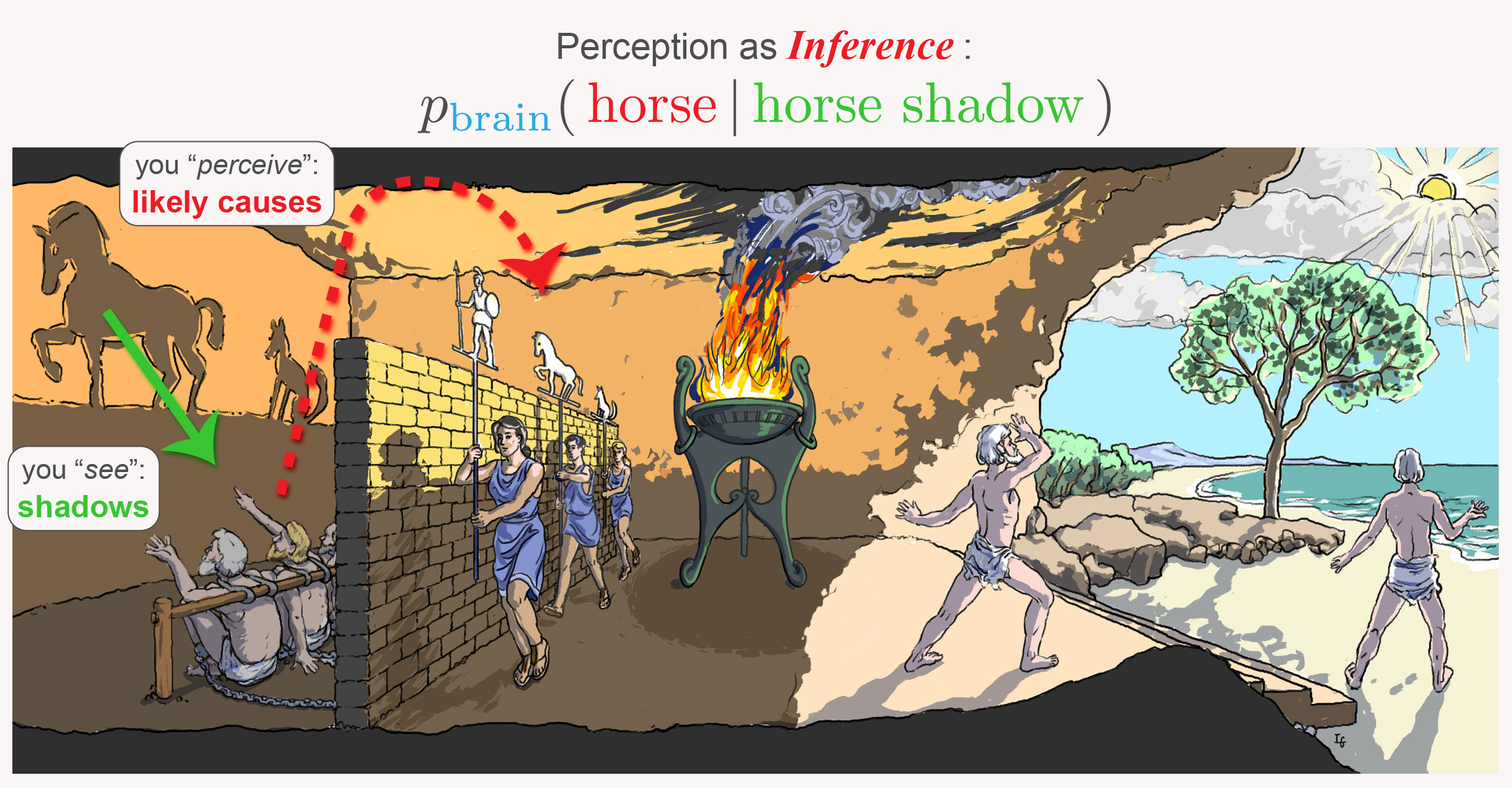

This idea that “perception ≠ reality” isn’t exactly new. Like every other cool topic, the Greeks had something timeless to say about this, too. In this case, it’s Plato and his Allegory of the Cave: over 2400 years ago, Plato argued that being alive is like being chained in a cave, forced to watch shadows on the wall[R12] (Figure 2).

We never have direct access to the full reality, out there in the world; but we receive shadows—projections of that reality—and this allows us to make inferences about it, here in our minds (Figure 2). And somehow, that’s been enough for us, not only to survive and reproduce, but also to split the atom and measure gravitational waves. A true masterpiece of evolution!

So there you have it. We’re all prisoners in Plato’s cave, making educated guesses about reality from shadows on the wall. You might read these lines and despair at the recognition that we may never fully understand the true nature of the physical reality out there. But that’s okay. This shows you’re curious. If so, then you’re one of the lucky ones.

Cherish this longing.

Conclusions

This was just a warm-up. We’ve only scratched the surface of what it means to build beliefs from evidence, and to understand others (and ourselves) using limited, messy data. Our journey began with the simple feeling of being uncertain, only to reveal that we were walking a path contemplated for millennia, at least since Plato first wrote of it around 380 BC. I can even imagine the cave people also thinking about posteriors, in some deep, pre-linguistic way.

In future posts, I’ll show you the math behind all this. But for now, I hope I’ve planted a seed: uncertainty is the raw material of perception, cognition, and thought. So the next time you feel uncertain, remember: it’s not a true antagonist, but a feature. It’s your electric meatball inference machine doing what it does best. It means you’re paying attention. It means you’re alive.

Stay tuned!

This is Part 1 of a series on Bayesian inference and perception. Part 2 will introduce Bayes’ Theorem, provide a visual proof, and apply it to both optical illusions and social perception (Figure 3).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to my colleagues and friends, Thomas Langlois, Dekel Galor, Jingyi He, Thelonious Cooper, Chrissie Chen, and David Theurel. Your feedback significantly enhanced this post 🙂

Thanks to Claude 4.0 and Gemini 2.5 Pro for helping me “refine” and “streamline” the text, and for their guidance with HTML and CSS.

Finally, thank YOU, my dear reader, for sticking with me till the end. I hope you learned something new, and this piqued your curiosity to learn even more. If you enjoyed reading this blog post, I’d love to hear what you inferred from it. Write me: Contact.

Download as PDF

You can download the PDF version here:

References

[R1] Thomas Bayes. “An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances”. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 53 (1763), pp. 370–418. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1763.0053. ↩

[R2] Pierre-Simon Laplace. A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Courcier, 1812. url: https://archive.org/details/philosophicaless00lapliala/page/n11/mode/2up. ↩

[R3] Francis HC Crick. “Thinking about the brain”. In: Scientific American 241.3 (1979), pp. 219–233. url: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24965297. ↩

[R4] Bruno A. Olshausen. “Perception as an Inference Problem”. In: The Cognitive Neurosciences (5th edition) (2014). Ed. by Michael Gazzaniga and George R. Mangun. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/9504.003.0037. url: http://rctn.org/bruno/papers/perception-as-inference.pdf. ↩

[R5] John Locke. An essay concerning human understanding. Ed. by Peter H. Nidditch. Oxford University Press, 1690. doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780198243861.book.1. ↩

[R6] Hermann Von Helmholtz. Handbuch der physiologischen Optik. Vol. 9. Voss, 1867. url: https://archive.org/details/handbuchderphysi00helm. ↩

[R7] Alhazen. Book of optics (Kitab Al-Manazir). 1011–1021 AD. url: https://archive.org/details/TheOpticsOfIbnAlHaythamBooksI. ↩

[R8] Noah D. Goodman and Michael C. Frank. “Pragmatic Language Interpretation as Probabilistic Inference”. In: Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20.11 (2016), pp. 818–829. issn: 1364-6613. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.08.005. ↩

[R9] Alan Hájek. “Interpretations of Probability”. In: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman. Winter 2023. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2023. url: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/probability-interpret/. ↩

[R10] Bruno De Finetti. Theory of probability: A critical introductory treatment. Vol. 6. John Wiley & Sons, 1974. doi: 10.1002/9781119286387. ↩

[R11] David Spiegelhalter. “Why probability probably doesn’t exist (but it is useful to act like it does)”. In: Nature 636.8043 (2024), pp. 560–563. doi: 10.1038/d41586-024-04096-5. ↩

[R12] Plato. Republic, Book VII. 380 BC. url: http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.8.vii.html. ↩

Footnotes

- If you have any practical tips for this particular inference problem, I’m all ears: Contact. ↩︎

- I’m exaggerating here for fun. But the fact that humanity has survived for so long is a testament to our extraordinary inference abilities. Especially in the realm of social and emotional understanding, where inference becomes most subtle, layered, and sophisticated. When we interact with other people, the most informative signals aren’t in the words we speak. They’re in the pauses, the things left unsaid, and the pieces of our inner world we choose to reveal through art. Some of us say more in a song than we ever would in a conversation. ↩︎

- At this point, I was tempted to go deeper, exploring how uncertainty interacts with our desires, fears, and hopes, making us act upon it. This is a fun topic, and a significant point of divergence between emotion-driven biological intelligence and emotionless artificial intelligence. So I’ll save that for another post. For now, let’s finish this arc by introducing probabilities (which is just math-talk for uncertainty). ↩︎

- Math is less threatening than feelings. ↩︎